Building a watch as a surprise gift

In the last year I have been building watches from parts. So far I have built:

- March 2019: A vintage style pilot watch based on a Swiss ETA 2824-2 automatic movement

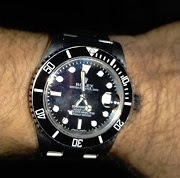

- April 2019: A replica Rolex Submariner also based on the ETA 2824-2 automatic

- May 2019: A replica Rolex Day-Date with a Sellita SW220-1 automatic movement

My eldest daughter and her husband had their first child, Lily, this year on October 15. Lily is Tara's first, my first grandchild, and my dad's first great-grandchild, making her the first child of her generation on the Reprogle side. As a result Tara's pregnancy has attracted a lot of attention.

Parenthood in general, and fatherhood in particular, is less highly valued by some these days. I strongly believe fathers play a crucial role in raising children, and I wanted to express that belief with a gift to encourage my son-in-law to be the best father he can be for Lily. Giving a watch also symbolizes how precious will be the short time he will spend with her as a child.

Planning for building a watch from parts starts with choosing the style of watch, whether sports watch like the Submariner or chronograph or a dress watch like the Day-Date. I wanted the gift to be a surprise, which makes it more difficult to choose a style, so I worked with Tara on the design choices. We decided on a classic design with a gold case and a vintage manual-wind movement, the Swiss Unitas/ETA 6497/6498.

The Unitas 6497/6498 was first produced in the 1950s as a relatively compact pocket watch movement. As a wristwatch movement, however, it is a large diameter at 36.6 mm. The smallest cases are in the 43-48 mm range, and are usually one of three categories, a classic dress style, an aviator style, or a Panerai style dive watch. Tara strongly preferred a classic-style dress watch in gold with a roman-numeral dial.

Finding a suitable movement was a priority, and I wanted an authentic Swiss Unitas/ETA movement with some decoration to give Matt (and others) something to admire as a piece of art and craftsmanship. I was excited to find someone selling the movement, dial, and hands from a 1960s-era Baylor pocket watch (below left). The 6498 was made in varying levels of finish from plain steel to gold to fully decorated, and the one I purchased features a hammered gold finish (below left).

Finding a suitable movement was a priority, and I wanted an authentic Swiss Unitas/ETA movement with some decoration to give Matt (and others) something to admire as a piece of art and craftsmanship. I was excited to find someone selling the movement, dial, and hands from a 1960s-era Baylor pocket watch (below left). The 6498 was made in varying levels of finish from plain steel to gold to fully decorated, and the one I purchased features a hammered gold finish (below left).

With the movement chosen, then next step was to select the case. Working with Tara I chose this 43 mm case with an 18k gold-plated finish, a display back to show off the movement, and a sapphire crystal to help prevent breakage or scratches. The crown is an "onion" or "pumpkin" shape which is a classic style to match the roman numeral dial. I used the original Baylor hands, which are Louis XIV style.

The eBay seller listed the 6498 movement as "running", which it did indeed do when I first received it. Since it was at least 45 years old, I assumed it needed cleaning, lubrication, and a new mainspring. Also, when installing a movement in a different case, you have to allow that the winding stem will need to be sized to a different length, so I ordered extra 6498 stems.

So the first step is the disassemble the movement for cleaning. The 6498 is relatively simple and large as watch movements go. When taking apart a movement I take photos along the way to help recall the positions of parts, screws, and springs during reassembly. I make notes on legal pad that doubles as a work surface.

Starting with the movement side, first part out is the balance assembly, then the train bridge and the ratchet wheel.

After removing some of the movement side parts, I flipped it over to work on the dial side parts. Most of the winding and setting mechanism is on the dial side.

Flipping back to the movement side, I removed out the barrel bridge and center wheel to expose the mainspring barrel, the silvery round part at 6:00. This contains the mainspring that stores the energy to drive the mechanism.

Opened and unwound one can tell this spring has lost much of its capacity by taking a set.

The parts went into the ultrasonic cleaner for several minutes.

They came out of the cleaner shiny and ready to reassemble.

I didn't get a photo of installing the new mainspring, mostly because I didn't have the right size spring insertion tool and had to hand-wind the new mainspring into the barrel, which I had never done before.

It was incredibly satisfying to put it all back together, align the balance wheel, give it a couple of turns on the crown to wind the spring and have the movement jump to life, kind of like doing CPR on a stunned bird.

Once the movement is running, it's time to check the timing and adjust or regulate it. I use software on the laptop with a spare PC microphone that listens to the ticking of the movement as the balance spins back and forth and measures the speed to estimate the rate accuracy in +/- seconds per day. A good number is something less than +/- 20s/d for a movement like this.

I was able to adjust it to +7 s/d in one position, which is very good, certainly for a 50 year old movement.

The timing was measured with the movement in 6 orientations. This one had quite a bit of rate deviation in the various positions (below), but there was not much I could do to eliminate it. It's probably due to wear from being old, like my knees.

The original Baylor dial (left photo below, top) was too small to properly fit the new watch case, so I ordered a vintage-looking roman dial (left photo, bottom) with nice sunburst pattern on the seconds subdial. The red XII is a classic design detail from Rolex military watches from WWI (below right).

The movement is mounted in the case, then the stem is cut to the right length, filed, and checked.

The crown is screwed onto the stem threads and secured with Loctite to help prevent being unscrewed if the crown is turned backwards.

The crown is screwed onto the stem threads and secured with Loctite to help prevent being unscrewed if the crown is turned backwards.While I was testing it on the wrist, the watch became an icebreaker when I was invited to my DC client's home for dinner. His 90 year old father was a doctor and a watch collector and immediately noticed the watch, said it was beautiful, and asked the brand. I replied that I had built it, which led to a conversation about my hobby.

The custom-made strap is from EShandcrafted, and Australian Etsy seller. A wood gift box with gold tone hinges completes the gift.

I set the watch to 9:27 to match the time that Lillian Josephine Randall was born on October 15, 2019.